Editor’s note: A previous version of this story included incorrect details about a meeting between John Oldham and WKU administrators as well as the years Clarence Glover played basketball at WKU. The article also mischaracterized comments made by Glover. The story has been updated, and the Talisman regrets the errors.

MORE TO GO

story by BETHEL AKLILU photos from WKU ARCHIVES

2020 has been an intense year. Along with an election and a pandemic, the year has included a notable resurgence in the Black Lives Matter movement following several instances of police brutality. Black history at WKU presents an opportunity to look at how national movements impact local changes.

Black history at WKU began 64 years ago when the university integrated in 1956. The first Black undergraduate student in WKU’s history, Margaret Munday, came to the Hill the following fall. Munday was the only Black student at the time and expected to face trouble when it came to dealing with Southern students.

In a 1996 interview with WKU alumnus Gene Crume, Munday explained that getting along with other students never turned out to be an issue.

“I didn’t have any problems,” Munday said. “Just as sweet as they could be.”

This transition was not without effort. During her time at WKU, Munday recalled a mysterious man she thought watched her at the bus stop every day, leaving at the same time she did. After notifying her family, they told her that the man was told to watch over her. She was unsure whether or not he was there for her safety.

More Black students began to arrive at WKU in later years. By 1963, there were 96 Black students enrolled and Black athletes began to be recruited.

Due to the racial precariousness of America at the time, 1971 was eventful for Black students at WKU. Black students across the country were driven by the civil rights movement to advocate for the integration of African-American studies courses in schools. Their dedication paid off as African-American studies, or Black studies as it was called at the time, became a course at WKU that same year.

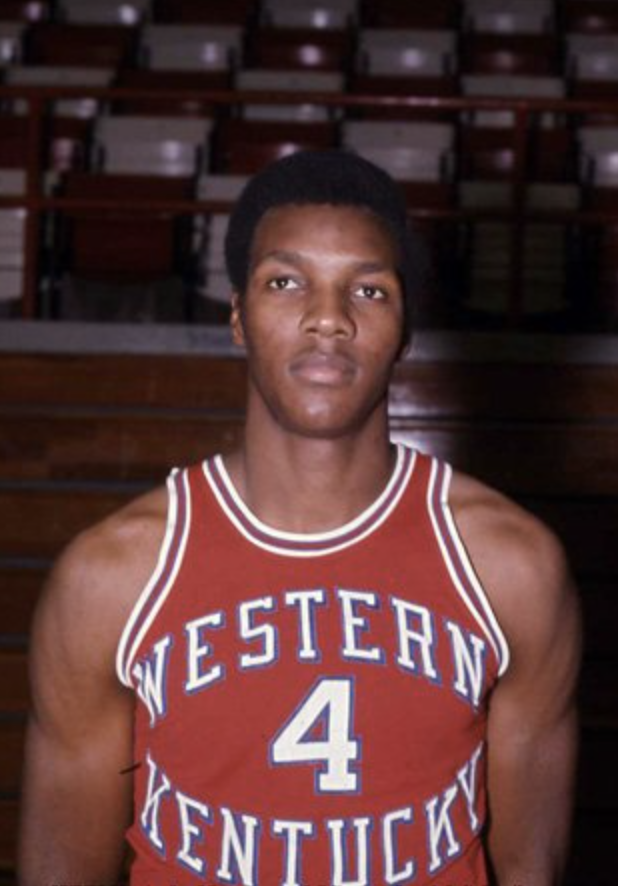

The same year, WKU’s basketball team had five Black starting players. The head coach at the time, John Oldham, received criticism and hate mail as a result. When a member of the Board of Regents expressed concern about the situation, Oldham was called into then President Dero Downing’s office for a meeting. Oldham said he planned to play five of his best players at the same time, and if they felt he should do otherwise, he would resign, said Clarence Glover, one of the five players and a current College Heights Foundation board director.

Glover credited Oldham for inspiring him to advocate for students of color.

Playing basketball at WKU increased Glover’s perspective of the world. Away games allowed him to see beautiful parts of the country he might not have seen otherwise.

He said he distinctly remembers a small hotel they visited every year in the South. It was an old hotel and the only one in town that would allow people of color inside. The ability to see how others around the country behaved around different people was eye-opening for Glover, and he considered these moments part of his WKU education.

Along with the integration of Black studies into the curriculum and the basketball controversy, 1971 included a cheerleading protest. Cheerleaders at the time were elected through a popular vote rather than judged by skill. Through the popular vote, only one Black cheerleader was elected.

Black student leaders discussed the issue with administrators three times, but they felt pursuing another avenue would be more productive. They decided to hold a sit-in at the lobby of the Wetherby Administration Building to protest from 8:30 a.m. to 1 p.m.

Former WKU President Dero Downing then went to the Board of Regents, who added three more cheerleading positions allowing another Black student to be elected. After this, it was decided cheerleaders would no longer be elected but rather undergo a series of tasks before a panel of judges to demonstrate skill, according to an article published in the College Heights Herald in 1972.

Glover dedicated a lot of his time at WKU to athletics. Though he did not participate in the advocacy for Black studies or the cheerleading protests, he was always supportive of students who pushed for equal and equitable opportunity.

“I was very pleased each time that there was something that took place that gave more inclusivity for girls and guys of color,” Glover said. “Because we’ve participated in everything in this country. From the times of slavery all the way through each of the wars, through the time that I was in school. And so therefore, my feeling was that if we’ve done all of those things to make this country, then it should include us.”

Glover said that because of segregation throughout the South, it was uncommon for Black students to have professors who were inclusive and treated them with respect. Glover recalled a time when he was a student at WKU where a professor told him that he was the best Black speech student the professor had ever had.

“I would rather be one of the best students you’ve had and not be categorized as the best Black student that you’ve had,” Glover said to his professor.

The African-American studies course soon evolved into a minor after Saundra Ardrey arrived at WKU in 1988. When she arrived, Ardrey was the only Black faculty member in the political science department.

“They didn’t know what to do with me, so they put me down on the second floor, and the department was on the third floor,” Ardrey said, laughing.

Eventually, Ardrey was promoted to chair of the political science department, a position she held for over a decade before giving up the position to teach at the University of Limpopo in South Africa for a year in 2017.

She, along with other African-American faculty and others who taught African-American centric classes in 1988, developed the curriculum for the African-American studies program. The faculty members were spread across several departments, including history, English, political science and sociology.

The department and its curriculum had a meaningful impact on students. Ardrey saw how courses like the African-American Experience allowed Black and white students alike to gain social consciousness and awareness.

As department head, Ardrey had control over the budget and wanted to direct more funds to organizations for students of color and support for their projects, creating a social environment that was welcoming, encouraging and inspiring for all students.

Ardrey feels as though classes centering around social issues should be a requirement for all students, not just an option when fulfilling Colonnade courses. Seeing the impact firsthand, she knows how transformative it can be to give students a space to participate in discussions they might never have otherwise.

For Black students, the African-American studies program allowed them to learn positive things about their history, strengthen their pride and create spaces for emotional support. With Ardrey’s help, many students were able to make friendships and expand their perspective.

“I require them to do things outside of the classroom, like go eat lunch together,” Ardrey said. “You know, when we go on trips, I make black and white students – I mix them up; I don’t let friends stay with friends. More than anything, when they come back, they have friends. And they understand that they’re just students, and everybody has different experiences and different backgrounds, different perspectives, but we’re all human. We’re all trying. They’re all trying to get through school. They’re all trying to make a success, and they’re all trying to do good.”

Despite this era of interpersonal progress, Ardrey thinks race relations are hardly improving at WKU.

“While I think Western means well, they, like other institutions, white institutions, struggle to know how to actualize what they believe,” Ardrey said.

Ardrey believes rehashing the same stories of racism and creating more diversity and inclusion committees deflect from true progress being made. She was on her first diversity committee in 1990. Now 30 years later, there are still committees being dedicated to the same diversity issues. Having continuous dialogue with little to no implementation of concrete solutions keeps from real change happening.

"... everybody has different experiences and different backgrounds, different perspectives, but we’re all human. We're all trying." - Saundra Ardrey

“We spend so much time making white friends feel good, that they are not racist, that there’s no racism, that we can’t even get to the solution. But we spend all our time making you comfortable with racism,” Ardrey said. “Here I am now, getting ready to welcome my grandchild, and we’re still talking about the same issues. For me and for a lot of my generation, that’s frustrating.”

Ardrey believes WKU could improve the situation by investing in its students and faculty of color. Financial and budgetary concerns have always been considered even before WKU’s fiscal struggles, but recently, the neglect of these groups has gotten worse. When it comes to budget cuts, services for marginalized students tend to be cut, Ardrey said.

Programs in place for marginalized students need to be strengthened and have diverse leaders. There should be more places where students of color feel supported, like the Intercultural Student Engagement Center, and more Black people in policy making roles, Ardrey said.

“Folks always say, ‘Oh we want a place at the table. We want a seat at the table,’” Ardrey said. “You know, that’s nice. I don’t want a seat at the table. I want to help build the table. I want to be at that level of being able to come up with strategies and tactics. And I think that perspective then often changes because sometimes whites don’t even know what questions to ask.”

Glover said there is still more work to be done for people of color at WKU and beyond.

“At the end of the day, the people that are in charge of the United States are the same gender as me but they don’t look like me,” Glover said. “And so, those are the people who have the money. Those are the people that decide what the people at the lower levels get to do, and as those changes take place, then changes take place at the university for students of color.”